A February 22, 2024 calendar picture and my subsequent mention of canoeing down the Yukon River today prompted Susan’s suggestion that I should do a blog on my experience on that river in 1971, so here it goes. Tom Kovacs with the Parks Canada Wild Rivers Project states in his article “The Wild Rivers Survey: 50 Years On”, “the trip became the precursor of the Canadian Heritage River System”. Just before their trip, as Head of National Historic Sites for Western Region of Canada ,I made a similar (but about 700 mile) trip, a combination by Canadia/USA park’s people and due to the threat of a massive dam/hydro project.

There were about eighteen of us in two flat stern canoes with small motors. My Superintendent of Historic Sites of Yukon had done an excellent job of arrangement of every thing; food packaged separately for each meal, motor fuel and sleeping bags stored safely, a renowned guide in Alan Innes-Taylor who had worked “on the river-boats and every twist and turn, the boats themselves and relics in the river or docked onshore; who had joined the Royal North West Mounted Police at aged nineteen and been posted in the Arctic. for my benefit, he was assigned to my boat because of his knowledge of the history. Most of the others were there to assess the natural environment.

Human occupancy of the Yukon Territory has always, from prehistoric times, been mainly along this river, but 53 years ago, there was only remanents of their presence left.

This is as much as Dad got written before his health took a turn for the worse and he couldn’t continue. I found what follows in his work “History is my Life” / Harry A. Tatro 1985? Pg 45-. I have not done more than minimal editing so you get it in his words.

A Measure of Bruce’s (Harvey) resourcefulness was amply demonstrated when we made a trip down the Yukon River, a distance of some seven hundred miles. It was a joint Historic Sites, National Parks and United States Park Service venture, with eighteen participants, to assess the potential for a Klondike Gold Rush International Park, contrary to a massive hydro-electric project proposal. The latter visualized a dam on the Yukon River to create a great reservoir, a tunnel through the westward mountain range to gravitate water poser on the steep Skagway slope. We Park types did not favour such development which would destroy important historical and natural resources.

Bruce organized the canoes and other equipment; the food carefully packed and marked “Breakfast, August 29th, etc. for every meal; arranged fuel for the small outboard motors; engaged a renowned guide in Alan Innes-Taylor; and every detail for the extended voyage. No military manoeuvrer was ever better planned or more efficiently executed than that memorable trip. No better guide could have been found than Alan Innes-Taylor. At nineteen years of age he had joined the Royal North West Mounted Police, had been posted to the Arctic where he had vast experience in frigid Climes, upholding the law, maintaining sovereignty, taking census, collecting customs, and all other such duties that fell to those stalwart men. During World War II he had a key involvement in a secret experimental ice aircraft carrier which was a complete success but developed too late to be used. He was also an advisor on Arctic survival to allied forces. Becoming familiar in the living rooms in many nations. He had returned to the Yukon, spending many years on the riverboats and thoroughly studied local history. He knew every rapid, shoal and curve of the river, every boat and where each had capsized or had experienced some incident of note. He could point out the stopping places for fuel-up where great piles of firewood had lined the banks. He knew the many settlements, how mostly abandoned, the residents of the settlements and what had happened to them. I was delegated to his, the leading, canoe and was privy to this wealth of information.

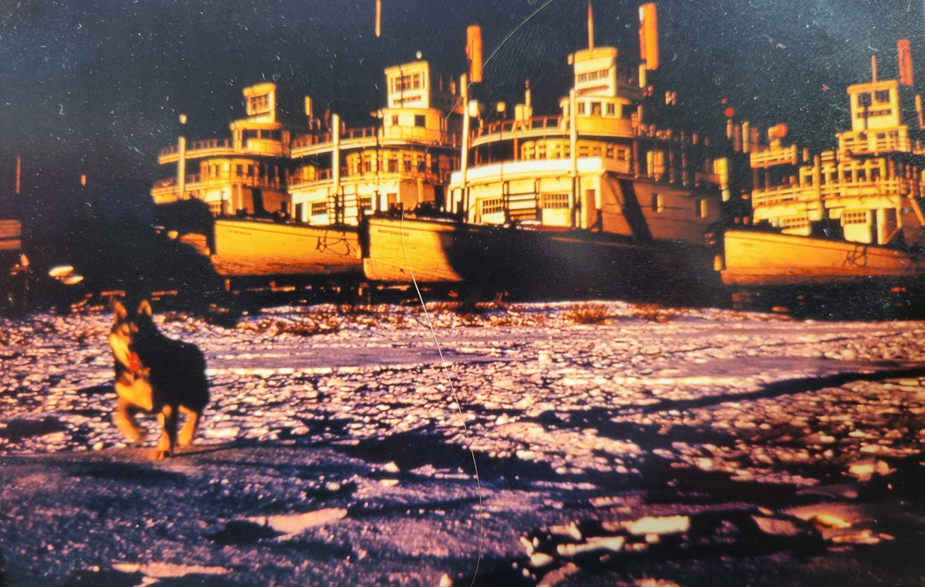

We launched the canoes at Lake La Barge, made famous by poet Robert Service in his “Cremation of Sam McGee”. Alan told of other stern wheelers, and we stopped to investigate the skeleton of one where she rested at the outlet of the lake. He told us also of how they used to spread oil on the ice of the lake, one end to the other, to open a channel for the steamers, for the river would open much before the ice would melt on the lake by natural means in the spring. This would accelerate the navigational season considerably but would be found quite unacceptable by modern environmental standards.

Human occupancy of the Yukon Territory has always, from prehistoric times, been mostly directly related to the Yukon River. Numerous cabins and settlements, all abandoned, were scattered the length of our trip, the people now being congregated in a few towns. There was Hootalinqua, Minto, Salmon, Ogilvie, and many more, all with their heaps of abandoned paraphernalia, their crosscut saw blades over windows to discourage marauding bears, their dog sleds leaning against the northern side of the cabin, opened-out gas can shingles, log cashes up on stilts at the back to keep the food away from thieving animals. Hours we spent exploring these while Alan told stories of heroism, murder, rescue, death, success and failure. At night while we ate a hearty meal we would sit around the campfire and listen to these stories of the north.

Bruce too had gained a number of tales of Indians and exploits which were as well told as Alan’s. When tired we rolled into sleeping bags under the stars. We just got to sleep one night when Bruce called, “Hey! If anyone is awake the northern lights are worth looking at.” Of course, everyone was awake by then but none, after looking, could fault Bruce for the awakening. The sky was a dome of dancing splendour, horizon to horizon in all directions. Perhaps it was only imagination but one could swear to hearing the crackle of the flashes. We did not mind loss of a little sleep to marvel at this overwhelming show of natures glory.

Alan had predetermined each campsite – you just don’t camp anywhere. There are good spots, and there are mostly bad spots. At Carmacks, one of the few places where we saw evidence of current man on the whole journey, we put up the tents for the only time. In the morning, they were stiff with white frost. While we shivered and dressed, then huddles around the campfire wrapped in parkas, I was almost disgusted with Bruce. There he was in short sleeved cotton tee-shirt, muscular biceps flexing over frying pans and biscuits, happily preparing breakfast in the half daylight, seemingly totally oblivious to the cold. I could have kicked him, but at the same time could not quell my admiration.

After breakfast we had to wait for the fog to lift for we had the Five Fingers Rapids to navigate soon after take-off. This was one of the most thrilling natural features of the trip. It had been equally thrilling for the riverboats. Cables and winches had eventually been installed to ease boats through this dangerous section. We shot through the tumbling shoot without mishap ,then in the lee of the rocks stopped to marvel at the swirling water, the four giant rocks dividing the stream and the honey-comb of swallow nests attached to them. The swallows had already left on their southern migration.

It was autumn and the whole Yudon River Valley was clothed in all of its many coloured splendour. As we passed mountain slope, cut bank, creek valley, or river mouth, one could never tire of the changing natural kaleidoscope of colour. Mile after mile of unending natural beaty hardly at all interrupted by modern man, just the infrequent evidence of his former presence. This was a wild river worthy of the attention of any avid naturalist.

At Fort Selkirk, opposite the mouth of the Pelly River, we slept inside the better of the abandoned buildings, each to his individual choice. Danny Roberta, a mostly native trapper with his family, were the only residents. He had a team of massive, vicious dogs that, judging from their attitude toward us, would have ripped us to pieces if they had not been securely tied at all times. They were splendid looking, well-kept animals, obviously capable of drawing a heavily loaded sled. The buildings and much of the material goods of former residents were more in place and in better condition here because Fort Selkirk had not been abandoned for long. Alan told the story of one on the Lamb boys of Lamb Airways, who delivered the mail by air. To save time he would fly low over the runway (now quite overgrown) and drop the bag and continue on his way. This one day his cap was whipped out of the open window. Unperturbed he circled around, Landed, recovered his cap and took off, to everyone’s amusement.

The schoolhouse was paradox of wilderness/civilization. There was the crude wood burning heater, had crafted disks to seat multiple students and primitive homemade facilities that on might expect in such a wilderness setting. Then there were the teaching aids such as the primary readers of “Dick and Jane” and their exploits on the big city streets. I wondered how appropriate were these elements do foreign to these students who probably had never experienced a city and if the teachers had any degree of success in planting the rudiments of reading and language. For educationalists our professionals can often appear mighty stupid.

We crossed the Yukon River to the Pelly and a mile from its mouth visited the Bradleys who operated the only real farm in the Yukon Territory. They had excellent Hereford cattle, good crops and a big garden including garden flowers and the biggest carrots that I have ever seen. I remarked on how easy it would be to irrigate their flat land lying along the wide river course. “But for what reason?” said one of the brothers, “It would increase our work and we have all we want now.” With their own Caterpillar tractor they had guilt a road out to the highway and thus were able to transport their produce to Whitehorse for market. This brought all the returns they desired.

Being situated so remotely, I was surprised at their knowledge of the outside world, their library and their guest book which read like “Who’s Who” in the world. A significant archeological dig had been done on their farm, which added to the knowledge of early man’s migration to this North American continent. After showing us the many reports and maps, we were guided to the dig site just above the wide alluvial flats. But the most outstanding thing about the farm was its museum-like quality. It had been in operation for about seventy years and like everywhere in the north, nothing ever leaves. There was the total evolution of farm machinery, from the oldest to modern day, all neatly arranged in a large machinery yard. Some of us with farm backgrounds could have spent hours examining it. Next to the machinery yard was the old log blacksmith shop. Sagging under its burden of tools and iron clinging and laying upon it. Maybe it was the mass within that kept it upright. Unfortunately, shortly afterward the blacksmith shop was burned to the ground losing most of those antique treasures.

We passed the White River mouth where the clear water in which we travelled suddenly, in a definite line, took on the milky ash of the ancient volcanic eruption. The riverbanks displayed the layer of ash which in some places was a couple of feet thick. Then there was the Stewart River where the trapper family, father, mother and son, each had abandoned ski-doos in the woods in favour of their more reliable fine dog teams. We passed by a clearing where an enterprising government had set up an agricultural experimental station, and just beyond there was the great landslide scare in the Dome. We were approaching the City of Gold named in commemoration of that rugged little hunch-back geologist, Goerge M. Dawson. Imagine the thoughts of the gold seekers who made that same trip downstream in raft, homemade boat or anything that would float in ’98! Past Lousetown we crossed by the mouth of the Klondike then docked at Dawson City. There we lined up on the bank for a group photograph.

The trips on to Eagle in Alaska was rather anticlimactic. Some of the party went by road to pick up the canoes, equipment and people at the voyage end. But it was not without both historical and natural interest. We stopped on an island at the home of Percy Dewolfe, who had been honoured by the Queen for his outstanding devotion to duty and endurance in carrying the mail without fail for many years despite weather and all other adverse conditions. The remnants of various sleighs, toboggans, boats and other transport conveyances lay scattered about. At Forty Mile we stopped to investigate buildings and other remains including the North West Mounted Police barracks where the gold discoverers had come to register their claims that started the greatest gold rush ever known.

Arriving at Eagle we could feel some sense of accomplishment and discovery in our trip but it seemed a bit of an embarrassment to mention it when surrounded by the reminders that here, years earlier, Roald Amundsen had arrived to announce to the world that he had returned from his successful journey to the North Pole.